Published October 28, 2019 • 7 Min Read

-

International investors continue to exit the oil sands

-

Capital investment in the oil and gas sector has fallen 15% below 2016 levels

-

Major pipeline projects remain mired in delays

-

National consensus on the development of our energy resources remains elusive

-

Fossil fuels will continue to account for ¾ of Canadian energy use in 2030

-

Global energy demand growth is creating opportunities for Canadian producers

Construction of the-long delayed Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion restarted this August after clearing some regulatory hurdles. Any enthusiasm the restart may have created in the oil patch was tempered by the passage of Bill C-69, which will overhaul the federal regulatory review process for major infrastructure projects and according to some in the industry, make it even more difficult to get additional pipeline capacity approved. Output caps put in place by the Alberta government to support the price of heavy crude remain in place.

Western Canadian frustration with developments that have hampered the growth of a key industry was laid bare in the October 21 federal election. The governing Liberals failed to elect a single MP from either Alberta or Saskatchewan, while parties opposed to additional pipelines received strong electoral support elsewhere. Amid the divisions, a recent Nanos poll showed nearly half of Canadians believe the country is doing a poor or very poor job of developing a shared, long-term vision for energy.[1] And 80% think the oil and gas sector can play an important role as long as it operates in an environmentally responsible way.

Energy Matters highlighted Canada’s potential to remain a key global supplier of oil and gas, with new infrastructure helping to tap fast-growing markets and diversify exports beyond the U.S. The benefits would include stronger economic growth, more jobs, and more royalty revenue to support the transition toward cleaner energy. The cost: higher domestic GHG emissions that will challenge Ottawa’s already-lofty goals of reducing emissions by 2030.

Read the Full Report

ENERGY MATTERS

Canada’s options for the 2020s

Global energy supply and demand

The EIA’s 2019 International Energy Outlook once again highlighted two key themes: global energy demand is on the rise, and the energy mix is becoming cleaner. Demand for nuclear and renewable energy is expected to increase by 37% in the next decade and make up more than 1/4 of energy consumption by 2030.[2] That’s up from the 21% share envisioned in the EIA’s 2017 outlook. The shift to renewables will be evident across regions.

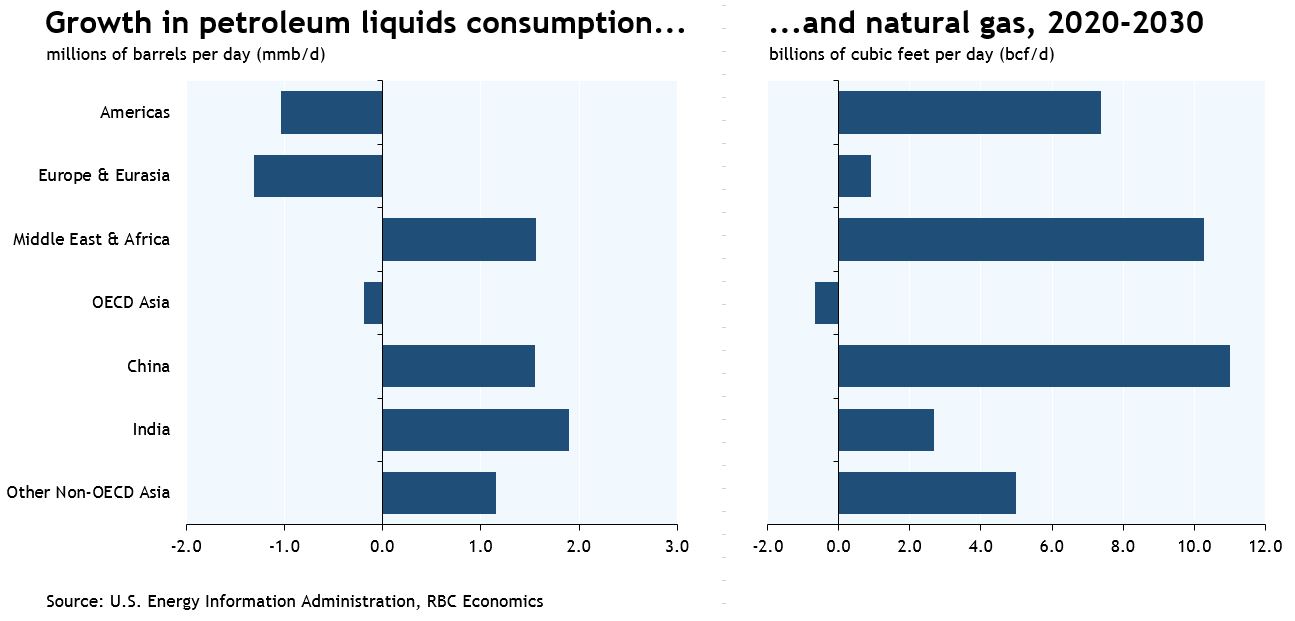

While clean energy is on the rise, demand for fossil fuels has not disappeared. Global petroleum demand is expected to rise by 3.6 mmb/d between 2020 and 2030. All of the demand growth will come from non-OECD countries — emerging Asian economies alone will need another 4.6 mmb/d of supply, equivalent to Canada’s entire production last year. Petroleum demand in the U.S., currently the destination for 96% of Canada’s oil exports, is expected to decline.

Natural gas will also see healthy growth, with global demand expected to increase by 10% in the next decade — an additional 36.6 bcf/d of production that represents more than twice Canada’s current output. As with petroleum, demand growth is concentrated in emerging markets though some advanced economies (particularly the U.S.) are also expected to increase consumption.

Supply growth will come from a few key producers. The EIA expects the vast majority of crude oil supply growth will come from OPEC and the U.S. The latter will also see the most significant growth in natural gas production, while the Middle East, Africa, and Russia will also chip in. An increase in LNG shipments means natural gas markets will become more globalized.

Canadian energy supply and demand

Like other advanced economies, Canadian energy consumption is expected to grow only modestly over the next decade. The Canadian Energy Regulator’s latest projections show domestic energy demand will increase by just 3% between 2020 and 2030. [3] Canada is expected to slightly reduce its consumption of refined petroleum products over that period with demand peaking in 2023. But natural gas is expected to be the country’s fastest-growing source of energy. That means fossil fuels will continue to account for roughly 3/4 of energy use in 2030. Demand for hydro and other renewables will grow at a solid pace, while nuclear energy use is likely to flatline.

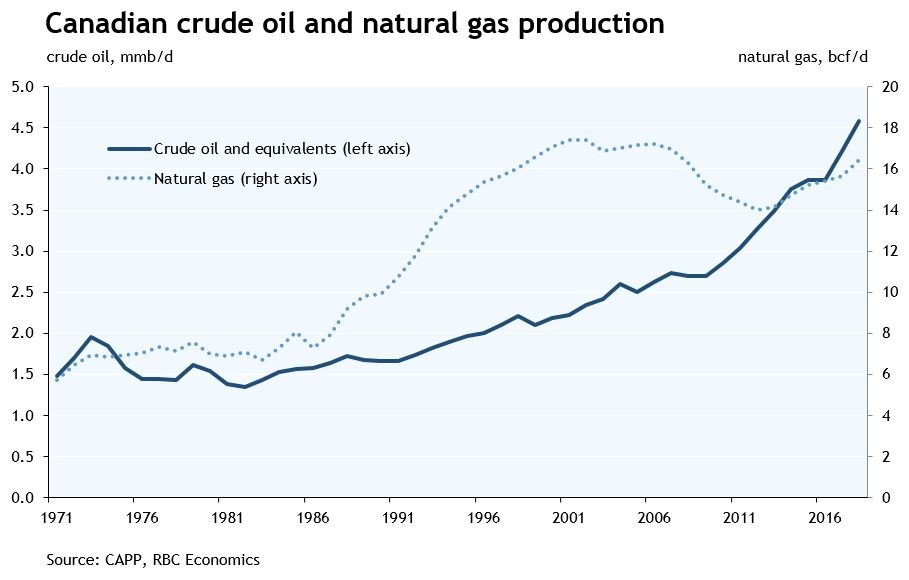

The real growth opportunities lie abroad. Canada has ambitions to export renewable energy technologies to other markets, aiding in the clean energy transition where demand growth is strongest. And there has been progress in that area—Canada exported more than $12 billion in environmental and clean tech products and services in 2017, a 50% increase from a decade earlier. [4] But the country can’t ignore its potential to export energy and not just energy technology. As we argued in Energy Matters, Canada can join global heavyweights in supplying more oil and gas to fast-growing markets. Canada is the world’s fourth largest producer of both crude oil and natural gas. Oil production grew by 9% in each of the last two years, hitting a record 4.6 mmb/d in 2018.[5] Meanwhile, natural gas production rose 5% last year, surpassing 16 bcf/d for the first time in a decade.

Production growth is increasingly bumping up against export capacity constraints, particularly in the oil sector. Crude-by-rail and Enbridge Line 3 replacement will provide some relief, but exporters will have to wait until mid-2022 at the earliest for Trans Mountain’s additional pipeline capacity. We continue to expect Canadian oil production will grow in the coming years as newer projects ramp up and expansion phases are completed. However, we don’t expect a repeat of the output growth seen over the last two years. Regulatory uncertainty and ongoing transportation issues have made it less likely that we’ll see the investment and production growth assumed in the “aggressive growth” scenario of Energy Matters.

Canada is also making slow progress toward expanding its natural gas exports. The LNG Canada project won’t be in service until the mid-2020s. And while two additional LNG projects have moved further along in the regulatory and permitting process over the last year, two others were cancelled. LNG will help Canada diversify its exports away from the U.S. which itself has become a net exporter of natural gas. Canada’s net pipeline exports to the U.S. are forecast to decline by 1.0 bcf/d between 2020 and 2030.[6] For comparison, LNG Canada’s first phase will add roughly 1.7 bcf/d of export capacity. A potential second phase of the project, which has yet to receive a final investment decision, would double that capacity and help Canada keep up with other major global producers.

GHG emissions

As we noted in Energy Matters, rising oil and gas production comes at a cost. Greenhouse gas emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector rose by 7 Mt in 2017, more or less accounting for all of the increase in emissions nationally.[7] While the sector has steadily reduced emissions per barrel over the last several decades, particularly in the oil sands, ongoing efficiency gains are needed to keep emissions from rising in step with production. Even in our baseline production forecast, GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector are projected to increase as output growth more than offsets trend-like efficiency improvement.

As the country’s highest-emitting sector — accounting for a record 27% of national emissions in 2017 — the oil and gas industry is often the target of calls to reduce Canada’s environmental footprint. But oil and gas producers aren’t necessarily the lowest-hanging fruit when it comes to trimming GHG emissions. There is potential for efficiency gains in areas like transportation, buildings, heavy industry and agriculture that could come at a lower economic cost than cutting back oil and gas production. That’s essentially what a carbon tax is designed to do — find the lowest-cost ways of reducing GHGs across sectors. The Liberals’ election win means carbon taxes will remain a central tool in Canada’s strategy to lower emissions.

Sources:

[1] The Globe and Mail, “On energy and environment, Canadian voters aren’t as divided as you may think,” October 17, 2019

[2] U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), International Energy Outlook 2019

[3] Canada Energy Regulator, Canada’s Energy Future 2018: Energy Supply and Demand Projections to 2040

[4] Statistics Canada, Environmental and Clean Technology Products Economic Account, 2017

[5] CAPP, Statistical Handbook Tables 03-10 and 03-16

[6] EIA, International Energy Outlook 2019

[7] Environment and Climate Change Canada (2019), National Inventory Report 1990-2017: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada

For more insights about social, economic and technological trends, please visit the RBC Thought Leadership website.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Any information, opinions or views provided in this document, including hyperlinks to the RBC Direct Investing Inc. website or the websites of its affiliates or third parties, are for your general information only, and are not intended to provide legal, investment, financial, accounting, tax or other professional advice. While information presented is believed to be factual and current, its accuracy is not guaranteed and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author(s) as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by RBC Direct Investing Inc. or its affiliates. You should consult with your advisor before taking any action based upon the information contained in this document.

Furthermore, the products, services and securities referred to in this publication are only available in Canada and other jurisdictions where they may be legally offered for sale. Information available on the RBC Direct Investing website is intended for access by residents of Canada only, and should not be accessed from any jurisdiction outside Canada.

Share This Article