TLDR

-

Joseph Tanel, a Cambridge, Ontario resident, recently replaced his gas furnace with a heat pump.

-

To reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Tanel researched heat pump options and installed a model suitable to his needs.

-

Since installing the heat pump, Tanel has helped friends and family make similar investments in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

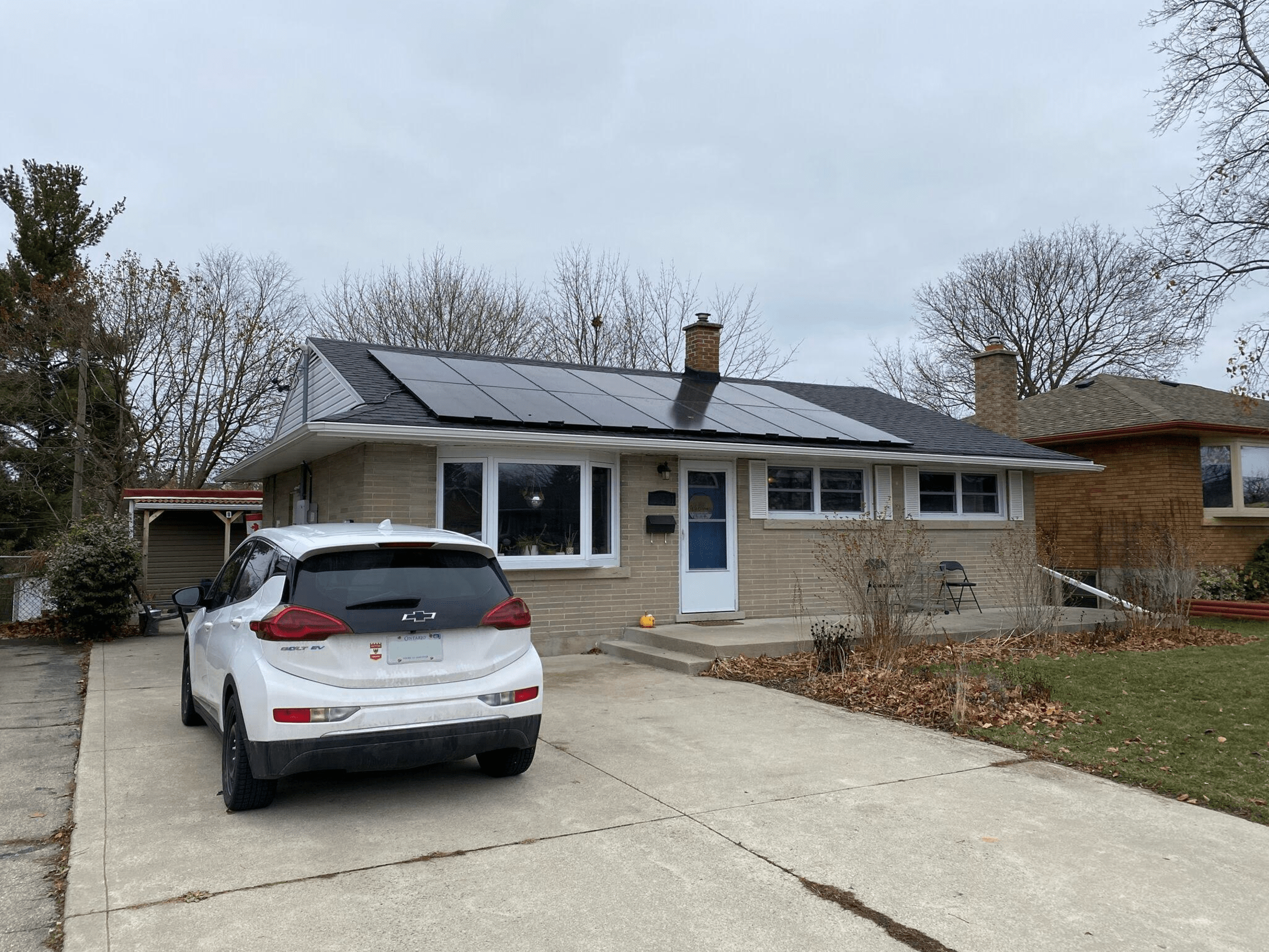

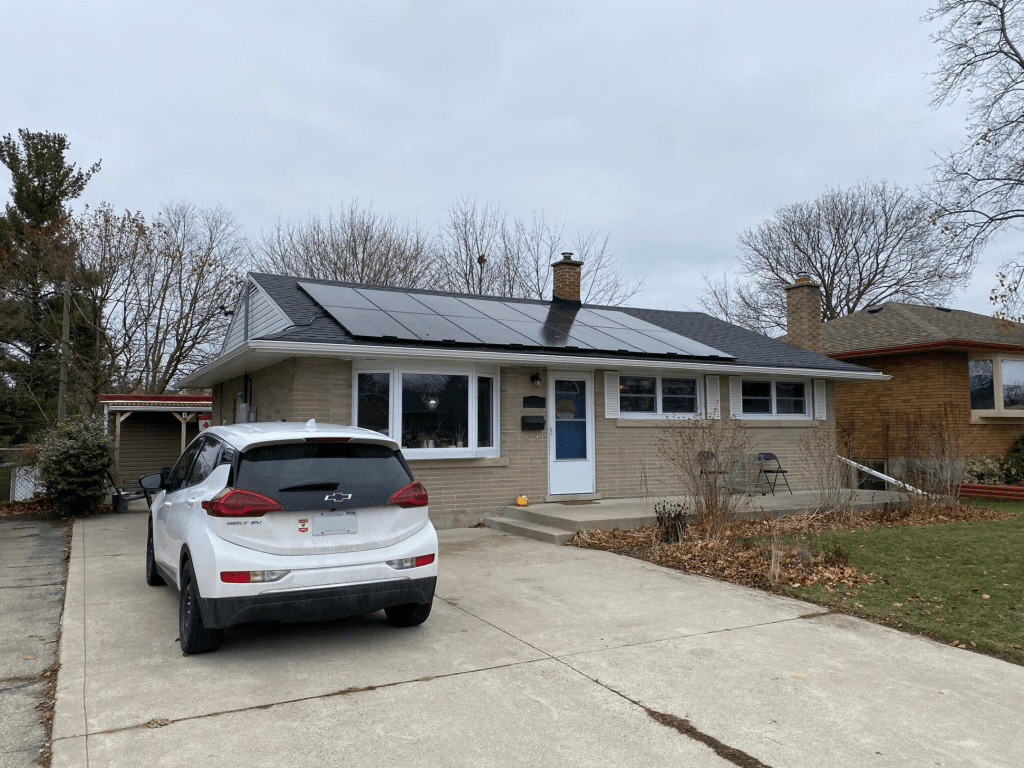

When Joseph Tanel first considered installing a heat pump in his Cambridge, Ontario home, he had one mission: To reduce his environmental impact. With more than half of homes still dependent on fossil fuels for heating, Tanel was, like many Canadians, concerned about the greenhouse gas emissions from the energy his home consumed throughout the year. Ninety-nine per cent of residential greenhouse gas emissions come from heating space and water.

Three years ago, Tanel, who works on RBC’s Climate & Sustainability Operations team, embarked on a mission to eliminate as many greenhouse gas emissions from his home as possible. His first steps included smaller home efficiency upgrades, such as installing LED light bulbs, a smart thermostat, and drain heat recovery to capture waste heat from his shower. “Then I moved on to bigger-ticket items,” he explains, replacing his gas-powered water heater with a hybrid heat pump water heater. But he had yet to address the most significant contributor to his home’s energy use: Heating and cooling.

Tanel’s next step was a heat pump. He knew it could significantly reduce emissions. Compared to gas furnaces, heat pumps are significantly more efficient. Not only do they emit fewer greenhouse gases, but in many cases, they can help lower energy bills. Tanel knew that a heat pump was on the agenda, but researching, installing, and living with a heat pump was a new experience for him.

Choosing the right heat pump

In 2022, he began researching his options. “It was still a new technology to me. It wasn’t too prevalent in my education, and I didn’t have many friends or family who were talking about it,” Tanel explains. He turned to the internet, conducted online research, looked at the data, and sought testimonials from heat pump owners.

In Canada, homeowners can buy geothermal heat pumps (less common), standard air-source heat pumps designed for lows of 0°C (typically installed with backup heaters for below-zero days), and cold climate air-source heat pumps, which can handle temperatures as low as -30°C. Homeowners, working with professional contractors, must do their due diligence to choose a heat pump that suits their budget, weather conditions, and personal preferences. Tanel chose a cold climate heat pump on the “higher end” of the pricing scale. “These days, I recommend heat pumps at a lower price point to friends and family,” Tanel explains, noting that many of the features in higher-priced models are now also available in mid tier-priced models from a range of manufacturers.

Buying a heat pump and applying for government programs

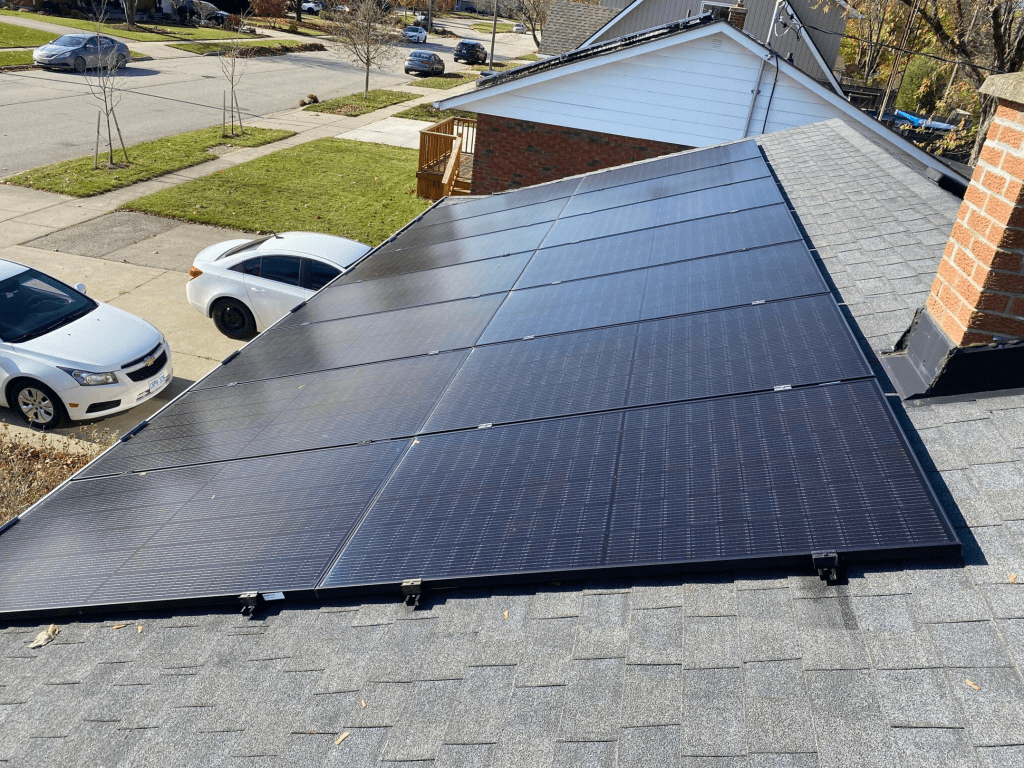

After selecting the desired heat pump equipment manufacturer, Tanel investigated his financing options. Several loans and rebates are available to Canadians who buy heat pumps. Tanel applied for the Canada Greener Homes Loan, which covers investments of up to $40,000 in energy-efficiency projects, interest-free for 10 years. Tanel used the loan to finance both his solar panels and heat pump, borrowing a total of $35,000.

Today, the upfront cost of a heat pump for a single detached home can range from $5,760 for a standard heat pump to $11,890 for a cold climate heat pump. They are typically more expensive than gas furnaces, priced at $3,750 to $4,170. Some homeowners may find the price points of heat pumps prohibitive. Still, the efficiency of heat pumps can lead to noticeably lower energy bills depending on your current heating system, local climate and other factors. Heat pumps also offer cooling — meaning they can replace air conditioners, which cost approximately $4,760 per unit.

Installing the heat pump

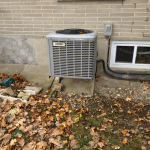

Tanel’s heat pump was installed in November 2022, approximately six weeks after he ordered it and scheduled the installation with the vendor. The installation process was much like replacing a furnace, involving “contractors and muddy boots” traipsing through the house. “There was a bit more prep work involved,” says Tanel. We needed the right space for the heat pump outside, and electrical capacity was our number one consideration.”

While heat pumps can be two to three times more efficient than oil, gas and electrical resistance heaters, if outside temperatures dip to a certain point, backup resistance heaters kick in. These can consume significant energy. Tanel’s existing electrical panel didn’t have the capacity to accommodate the backup heaters, so he had to upgrade it.

However, the upgrade was also necessary to install solar panels and an electric vehicle (EV) charger, two other items on Tanel’s energy-efficiency list, so this additional step didn’t stop him from moving ahead with his heat pump plans.

Living with a heat pump

What’s it like living with a heat pump? “It’s much more comfortable,” Tanel says. “Our old gas furnace was so loud and constantly cycled on and off.” In contrast, Tanel’s heat pump operates continuously as needed. “It just hums along,” he says, noting that “the noisy parts are outside.” The benefit of a unit that runs constantly is that the flow of conditioned air is also constant, significantly reducing hot and cold spots throughout the home.

Heat pump performance in cold weather

When considering life with a heat pump, many Canadians ask: Can it handle the depths of winter? Because heat pumps work by extracting heat from outside and transferring it inside, it’s hard to imagine this process working well in Canadian winters. But even below freezing, there is still heat in the atmosphere, and heat pumps can still function. Indeed, cold-climate heat pumps heat homes in temperatures as low as -30°C.

The backup electrical resistance heaters turn on if temperatures drop too low. Depending on their size, these backup heaters may increase energy bills on the days they turn on. Tanel’s heat pump came with backup electrical resistance heaters, but he has now experienced two winters without their turning on. Some homeowners choose to keep their existing gas furnaces as backup for ultra-cold days.

Potential savings on energy bills

Before he installed solar panels and a heat pump, Tanel’s electricity bills averaged $1,469 per year, while his gas bills averaged $658 per year. In 2023, with his solar panels and heat pump installed, Tanel spent just $807 on electricity for the year (just over half the amount of previous years) and $0 on gas, adding up to approximately $1,320 in savings every year. By his own estimations, the heat pump alone accounted for an 80 percent reduction in Tanel’s household greenhouse gas emissions, which would likely have netted him savings even without the solar panels installed. Heat pump maintenance is necessary at least once a year, or twice if used year-round for heating and cooling. So far, Tanel hasn’t required additional heat pump servicing.

Will heat pumps put more strain on the electrical grid?

Another question many Canadians have is: Can the grid handle the increase in electric use if homeowners continue to switch to heat pumps and electric vehicles? This transition will require a more robust electricity grid than Canada has, but with the right upgrades, the grid should be able to support widespread residential electrification. In Tanel’s case, his simultaneous solar installations mean he relies on the grid far less.

For Tanel, installing a heat pump was a no-regrets decision. “It’s a fun thing to talk about,” he says. “People come by the house just to have a look at it. And we’re happy when it’s running because we know it’s not producing any direct emissions.”

More advice for homeowners

Tanel’s home’s decarbonization journey is now complete. “The journey for this house started from scratch,” he says. “It had 100-watt lightbulbs and was running on gas-powered appliances.” Now, the home is fully electrified and powered by rooftop solar panels—a 180° transformation. Tanel has since helped his grandmother install solar panels and his father-in-law install both solar and a heat pump. Friends, too, have upgraded to heat-pump water heaters on Tanel’s advice.

Only 7 percent of Canadian homes have heat pumps, but many more will be needed if Canada is to achieve its 2050 net-zero target. “A lack of information is definitely impeding the adoption of heat pump technology, but it’s not something to be afraid of,” Tanel says. “Most new EV’s have a heat pump; dryers now have heat pumps these days — it’s where the world is moving given how efficient they operate and how they can be powered by renewable electricity.”

With so many friends and family members asking him for insights on heat pumps, Tanel has some advice: “Do your research, ask questions and learn all you can. It’s a great technology that can help you save money and be more comfortable. The most important step, is to act.”

Learn more about heat pump rebates and grant programs available in your province.