Published November 26, 2024 • 7 Min Read

Tapping into agronomic services can help empower farmers to make meaningful change by supplying them with a greater understanding of their land and its unique characteristics, improving harvest outputs and ultimately helping to reduce costs. Woodrill, a full-service crop input supply company offers a suite of agronomic services, including a unique soil mapping that goes deeper than the current provincial standard.

Luke Hannam has his work cut out for him. The 26-year-old is from a line of innovative agriculturists in Ontario, the fifth of his generation to farm this region. Today, he operates Woodrill Farms alongside his father, Greg, where they run a full-service crop input supply company. In a way, it’s just family tradition. In the 1960s Hannam’s great-grandfather switched the operation to strictly cropping, deleting the dairy arm entirely. It was a novel idea at the time; everyone had a mixed operation of some kind and there wasn’t the same segregation that exists between cropping and livestock as there is today. In the ’80s, his grandfather started growing seed and opened a crop supply branch, transforming the traditional family farm into a more modern agricultural business.

“He was always trying new things and probably went through a dozen different crops before he figured out that soybeans were going to be the next big Ontario crop,” says Hannam. “He bred his own seed and figured out how to make varieties for the Ontario climate. It was the inception of the soybean market for the province.”

That idea led to the formation of a seed company in cooperation with a dozen other farmers, backed by a breeding program and seed cleaning plant in Guelph to clean, package, treat and distribute seed across Ontario.

By the 1990s, the Woodrill’s skyline featured a grain elevator and a fertilizer tower as well, the height of farming at the time. Its agronomic services were in full swing, providing inputs like seed and fertilizer to fellow farmers in the region and introducing a new crop that hadn’t been grown on a large-scale in the area before.

“That was probably our earliest start in agronomic services, and it has blossomed from there,” says Hannam.

While it might seem daunting, Hannam is well on his way to making his mark on the family legacy. Today Woodrill is contributing to Ontario’s farming industry with its ever-evolving agronomic services. Divided into four sectors, its current agronomic offering includes fertility, seed, crop protection and precision agriculture, with the latter having a direct impact on the first three.

“Precision agriculture is a bit of a buzzword, but what it really boils down to is that every field and every part of that field is different, in soil type and geography, weather and water, and all of those things that go into the abiotic factors that make a crop,” says Hannam. “If the fields are all different and produce different levels of crops and have different outputs, we need to manage them differently.”

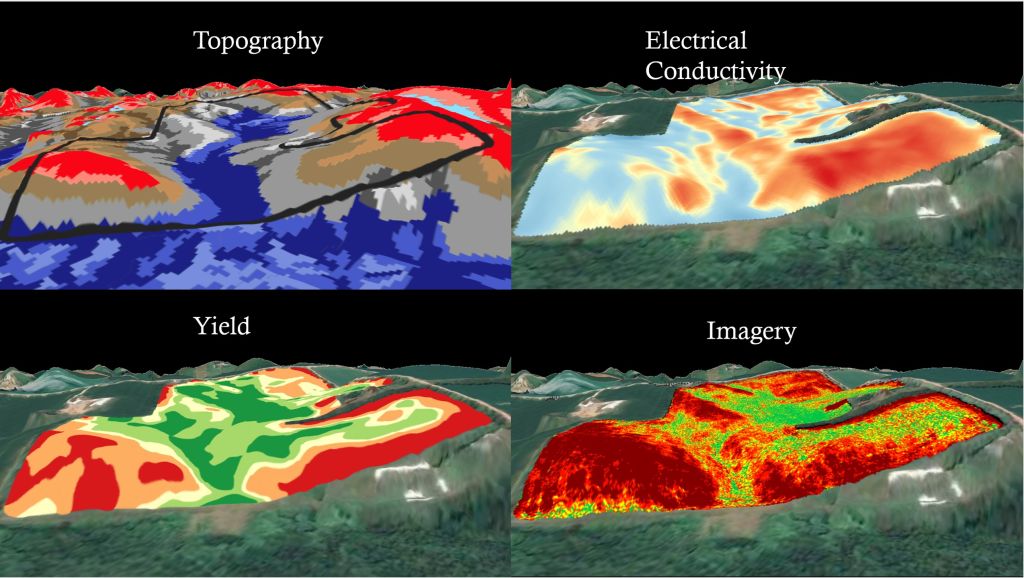

The first step to precision agriculture is to gather as much information as possible to better understand why one part of a field is behaving differently than another, then treat them accordingly. Woodrill uses a four-step approach to build robust maps of its clients’ fields and track corresponding behaviours.

The process begins with an electrical conductivity test performed by pulling a mechanical sled across a field. The device sends electricity into the soil and calculates how long it takes for it to bounce back, thus producing a map with many georeferenced data points.

“This paints us a picture of what a field’s variability looks like,” says Hannam. “If they behave similarly or differently, or have a similar electrical conductivity value, then we can assume that that part of the field is similar to another part of the field that has the same electrical conductivity value.”

Next, a soil coring machine penetrates the earth to the depth of one metre and collects soil for analysis at the on-site lab. Woodrill is the only company in Ontario to inspect soil health from this depth. They believe it helps give an understanding of how water moves (or doesn’t move) through the different soil types, and provides a robust map along with detailed reports on soil type, texture, organic matter and nutrient contents.

The current industry standards of retrieving soil from just 10 cm below surface, on the other hand, gives a basic nutrient analysis and is therefore important, but it often doesn’t reveal what’s going on below the surface.

Once the soil core has been collected, it’s given a name with the same nomenclature that has been used in Ontario since the 1950s to differentiate soil types, and is associated with a geographic area based on the electrical conductivity map, topography and yield maps.

“From there, everything is combined, and we make a final management map,” says Hannam. “This is important because precision agriculture mapping like this encapsulates our other agronomic services, including fertility, seed and crop protection products, and we’re able to build a map of how to most efficiently utilize our other services. We can sell you fertilizer, sure, and you can do whatever you like with it, but we can also build you a detailed map on how you should apply your fertilizer, how much of it to use and where you should put it.”

In addition to supporting planting, growing and maintenance decisions, precision agriculture also positively impacts the bottom line for many farmers.

“With our current situation in the agricultural economy, with suffering commodity prices and always increasing input costs, as farmers, we need to watch how much we’re spending and how much potential income there is on a per acre basis,” says Hannam. “Being able to manage each farm, or each portion of the farm independently from one another, we can more closely monitor our revenue stream on a smaller unit area than we previously could. We can come up with a dollar per acre number to make educated decisions. We’re not guessing anymore and making averages and generalizing a decision on 100 acres anymore. We can do it down to a tenth of an acre scale and make sure that we’re utilizing every dollar to its fullest extent.”

Precision soil mapping is also influencing field drainage, a critical component of sustainable agriculture. In the past, farmers would choose an arbitrary number to tile (aka drain) a farm, Hannam says, be it 10-, 20- or 40-feet., adding that “it’s the way we’ve done it since the tile drain was invented.” The in-depth information now made available from precisely mapping the topography and soil types is empowering farmers to better determine which areas of their land have the most economic response to tile drainage and where to place it.

“This has been something we’ve been exploring in the last year or two: how can we come up with a tile drainage design that is directly tied to agronomic data?” says Hannam.

Most prospective clients Hannam encounters are excited to garner more detailed information about their land, particularly in the face of climate change.

“Farmers are innately tied to the environment. We’re at the mercy of Mother Nature all the time and soil and water are the two biggest influences on our economics,” says Hannam. “There is definitely concern for the environment any time we make a management decision and being able to utilize as much information as possible to make an educated decision is a great thing.”

Precision agriculture means farmers can predict exactly how much fertilizer a crop will require in a specific area and then apply exactly that much. The idea is to save costs and improve environmental health by reducing the over-application of fertilizer while at the same time maximizing crop yield by not under-applying either.

“When used correctly, agronomics means we’re able to make educated decisions,” says Hannam.

From its position in the ever-evolving Canadian agricultural industry, Woodrill seems well situated to continue research in this and other areas of interest. You might say it’s their familial duty. You might just say it’s good farming.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Share This Article